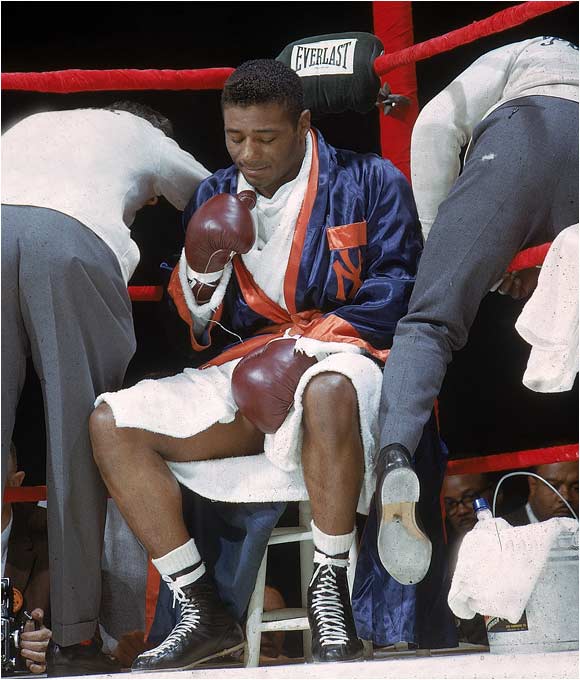

| Floyd Patterson, a gentleman

boxer who emerged from a troubled boyhood to become the world

heavyweight champion, died yesterday at his home in New Paltz, N.Y. He

was 71. The cause was prostate cancer

and Alzheimer's disease, said a grandson, Kevin McIlwaine.

In the 1952 Helsinki Olympics, Patterson won

the middleweight gold medal with five knockouts in five bouts. Then,

in a 20-year professional career, he won 55 bouts, lost 8 and fought 1

draw. His total purses reached $8 million, a record then.

He won the heavyweight title twice, knocking

out Archie Moore and Ingemar Johansson. In the first instance he

became the youngest heavyweight champion up until that time; in the

second, he became the first fighter to regain the title. He also lost

the title twice, defended it successfully seven times and failed to

regain it three times. He generally weighed little more than 180

pounds, light for a heavyweight, but he made the most of mobility,

fast hands and fast reflexes.

He was a good guy in the bad world of boxing.

He was sweet-tempered and reclusive. He spoke softly and never lost

his boyhood shyness. Cus D'Amato, who trained him throughout his

professional career, called Patterson "a kind of a stranger." Red

Smith, the New York Times sports columnist, called him "the man of

peace who loves to fight."

Patterson acknowledged his sensitivity.

"You can hit me and I won't think much of

it," he once said, "but you can say something and hurt me very much."

W. C. Heinz, the boxing columnist, found a

fundamental difference between Patterson the fighter and Patterson the

person.

"In expressing himself as a fighter," Heinz

wrote, "Patterson knows almost complete security. Outside the ring, he

knows no such security. A shy, sensitive soul-searcher, he volunteers

little. He might be called a conversational counterpuncher. When he

does speak out, however, it is with a purity reminiscent of Joe

Louis."

Floyd Patterson (he had no middle name) was

born Jan. 4, 1935, in a cabin in Waco, N.C., the third eldest of 11

children. His father, Thomas, was a laborer and his mother, Annabelle,

was a domestic who later worked in a bottling plant until the family

moved to the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn.

Above the youngster's bed was a picture of

him with two older brothers and an uncle, all boxers. Referring to

himself, he often told his mother, "I don't like that boy," and once

he scratched three large X's over his face in the picture.

He became a frequent truant who fell behind

in school. At 11, he could not read or write. He would not talk, and

when someone talked to him, he refused to look that person in the

face.

His mother had him committed to Wiltwyck

School, a facility in upstate New York for emotionally disturbed boys.

His new teachers helped him learn to read and encouraged him to take

up boxing there, which he did.

A year and a half later, Patterson returned

home. He attended Public School 614 for maladjusted children and

Alexander Hamilton Vocational High School before quitting after one

term to help support his family.

At 14, he started working out at the Gramercy

Gym on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, a battered facility owned and

run by the iconoclastic D'Amato. In 1950, he also started boxing as an

amateur. In 1951, Patterson won the New York Golden Gloves open

middleweight title. In 1952, after his Olympic success, he turned

professional.

His first pro bout earned him only $300, but

by 1956 he had become a leading heavyweight. When Rocky Marciano

retired that year as the undefeated champion, Patterson was matched

against Moore, the light-heavyweight champion, for the heavyweight

title.

For the fight, on Nov. 30 in Chicago Stadium,

Patterson rode to the event with Sam Taub, the veteran broadcaster and

reporter. As Taub recalled, "He sat there gazing out of the window

like he was going to the movies."

When they arrived, Patterson put on his

trunks, socks, boxing shoes and robe, stretched out on a rubbing table

and went to sleep. A few hours later, he stopped the 42-year-old Moore

in five rounds and, at 21, became the youngest heavyweight champion to

that point.

Patterson defended the title willingly but uncomfortably. In 1957,

he knocked out Pete Rademacher in six rounds in Seattle, and in 1958

he stopped Roy Harris, who was known as Cut 'n Shoot, in 12 rounds in

Los Angeles after both fighters had knocked him down.

On June 26, 1959, at Yankee Stadium, Patterson lost the title when

Johansson knocked him down seven times before the referee stopped the

bout in the third round. But he became the first heavyweight to regain

the title when he knocked out Johansson in the fifth round at the Polo

Grounds on June 20, 1960. "It was worth losing the title for this,"

Patterson said. "This is easily the most gratifying moment of my life.

I'm champ again, a real champ this time."

Patterson and Johansson met in a third title fight on March 13,

1961, in Miami Beach. After being knocked down twice, Patterson

knocked out Johansson in the sixth round, although some ringsiders

thought Johansson had climbed off the canvas by the count of 10.

The boxing historian Bert Sugar said by telephone yesterday: "You

try to tell people how kind Patterson was and how difficult it was to

reconcile that with boxing. In their second fight, Patterson knocks

him silly, then picks him up and drags him back to his corner. I've

never seen anything like that in the world of sports."

The glory days ended with Patterson's two title fights against

Sonny Liston. On Sept. 25, 1962, in Chicago, Liston knocked out

Patterson in the first round and became the champion. An embarrassed

Patterson drove home wearing dark glasses and a fake mustache and

beard. But he insisted on a return bout because, he said, "If I

stopped now, that would be running away."

"I did that when I was a kid," he added. "I've grown out of that."

The return bout came on July 22, 1963, in Las Vegas, and the result

was the same — Liston by a knockout in the first round. Patterson kept

fighting after that, but never at his championship level.

In 1965 in Las Vegas, with Patterson hiding a back injury, Muhammad

Ali all but tortured him before winning in 12 rounds. In 1970 in

Madison Square Garden, Ali opened a seven-stitch cut over Patterson's

left eye and beat him in seven rounds.

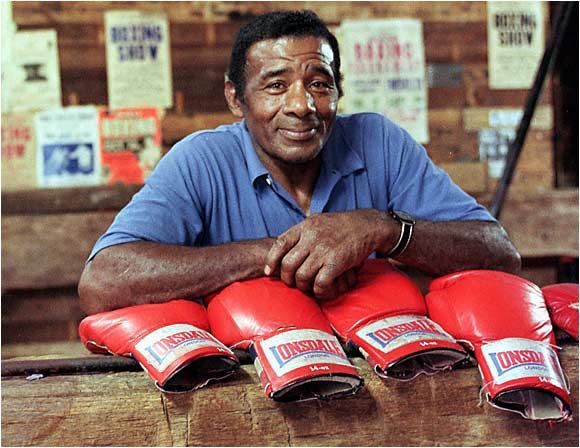

After Patterson finally retired in 1972, he became a respected

frontman for his sport. In 1983, he told a Congressional subcommittee:

"I would not like to see boxing abolished. I come from a ghetto, and

boxing is a way out. It would be pitiful to abolish boxing because you

would be taking away the one way out."

From 1977 to 1984, he was a member and from 1995 to 1998 the

chairman of the New York State Athletic Commission, which supervised

boxing in the state. He led a successful campaign to have the state

mandate thumbless gloves and thus reduce eye injuries.

In April 1998, while giving a deposition, his short-term memory

failed. He could not remember the names of his two fellow commission

members or his secretary or office routines. He resigned the next day.

Patterson is survived by his wife, Janet, whom he married in 1965;

their two daughters, Jennifer Patterson of Kingston, N.Y., and Janine

Patterson of New Paltz; and an adopted son, Tracy Harris Patterson, of

Highland, N.Y., whom he guided to the World Boxing Council's

super-bantamweight title in 1992. He is also survived by two sons and

two daughters from a previous marriage, Floyd, Eric, Seneca and Trina;

three brothers, Sherman, Raymond and Alvin; two sisters, Deanna and

Carolyn; and eight grandchildren. Further information about those

family members was not available.

Patterson was voted into the United States Olympic Committee Hall

of Fame in 1987 and the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1991. The

public loved him. As Dave Anderson wrote in 1972 in The Times:

"He projects the incongruous image of a gentle gladiator, a martyr

persecuted by the demons of his profession. But his mystique also

contains a morbid curiosity. Any boxing fan worth his weight in The

Ring record books wants to be there for Floyd's last stand. Until

then, Floyd Patterson keeps boxing, the windmills of his mind turned

by his own breezes." |

![]()